OBITUARY

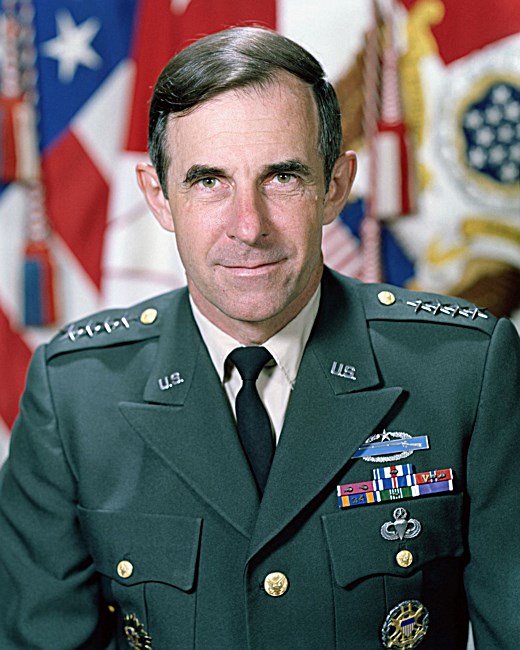

Gen. Edward Charles Meyer

11 December, 1928 – 13 October, 2020

by Matt Schudel

Edward C. Meyer, a four-star general who, as the Army chief of staff from 1979 to 1983, led an effort to restructure what he called a “hollow Army” in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, died Oct. 13 at his home in Arlington, Va. He was 91.

The cause was complications of pneumonia, said his son Tom Meyer.

Gen. Meyer, whose nickname was “Shy,” was a combat veteran of both the Korean and Vietnam wars before being selected as chief of staff, the Army’s top general, by President Jimmy Carter in 1979. He was moved ahead of at least 15 higher-ranking officers and, at 50, was one of the youngest chiefs of staff in history.

“He’s extremely energetic — the kind of guy who comes in on an overnight flight from Europe, shaves at the officers’ club and puts in a full day’s work,” then-Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Danzig told the New York Times in 1979.

During a congressional hearing in 1980, Gen. Meyer used the memorable phrase “a hollow Army” to describe how the military branch had been beset by staffing problems, outdated equipment and general malaise after the Vietnam War.

After Ronald Reagan became president in 1981, military funding increased, and Gen. Meyer led an effort to modernize the Army and raise the readiness and morale of troops. When he took over the Army’s top post, he said only six of its 10 divisions at the time were combat-ready.

Almost half of the Army’s 750,000 troops were overseas, leaving many stateside units threadbare or depleted. The Army had a shortage of sergeants and reserve officers, and unit leaders were rotated so often that they scarcely got to know the troops under their command.

In Gen. Meyer’s first year on the job, more than 20 senior generals retired or were replaced, easing the way toward new approaches to the Army’s internal organization and procedures. It was essential, Gen. Meyer said, to create a “vision of where we were going so that we weren’t trapped, as armies in the past have been, into just being a mirror of the kind of army we were before.”

He came to terms with the post-Vietnam, all-volunteer Army, although he would have preferred a return to military draft.

“I have great concern about the future of a nation in which there is no responsibility for service placed upon the people,” Gen. Meyer told the Times in 1983.

“Soldiers should not go off to war without having the nation behind them,” he said. One of the lessons of Vietnam, he added, was that “it became quite clear that the will of the people, the resources of the nation, and the Army weren’t clearly linked in that war.”

Gen. Meyer sought to improve the pay and educational benefits for enlisted service members and noncommissioned officers, which helped in recruitment. He toughened the Army’s training requirements, adding two weeks to basic training and an hour to each day’s drills.

One of Gen. Meyer’s most notable innovations was the “cohort program,” which kept company-size units, generally consisting of about 120 troops, relatively intact for three years, creating greater cohesion. He used a similar approach for larger units of 1,000 soldiers or more, maintaining stability when they were deployed to bases abroad.

Some changes that seemed minor to outsiders — such as allowing members of airborne units to wear distinctive burgundy berets — helped boost esprit de corps.

Throughout his four-year tenure as chief of staff, Gen. Meyer sought to modernize the Army’s weapon systems, moving away from the heavy tanks built for the Cold War to lighter and more mobile vehicles and equipment.

He often said there was little agreement between Congress and the Reagan administration on military priorities, which led to budget battles and conflicting demands over which weapon projects should move ahead or be shut down.

Nonetheless, Gen. Meyer was credited with raising the Army’s professionalism and developing a system that would allow for faster, more flexible deployments, as evidenced a decade later in the Desert Storm operation during the 1991 Persian Gulf War.

“Shy Meyer was a critical figure in the transformation of the Army from the dispirited, troubled post-Vietnam force to the professional and superbly trained and equipped Army of Desert Storm,” Eliot A. Cohen, a former State Department official and now dean of the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University, told The Washington Post. “And he was, in addition, a wise, humane and humble leader who served his country honorably and well.”

Edward Charles Meyer was born Dec. 11, 1928, in St. Marys, Pa. His father was a banker, his mother a teacher.

Tall and athletic, the future general was nicknamed “Shy” apparently because it was the opposite of his talkative, outgoing nature. He was an Eagle Scout and was inspired to pursue a military career by an uncle who had attended the U.S. Naval Academy.

At the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, N.Y., from which he graduated in 1951, he was captain of Army’s national champion lacrosse team and was a two-time all-American.

As a young officer, Gen. Meyer served in the Korean and Vietnam wars. He was awarded the Bronze Star and Silver Star for actions in Korea and the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross and Purple Heart in Vietnam, where he served in 1965 and again in 1969 and 1970.

He attended many specialized military training programs, including the National War College, and received a master’s degree in international affairs from George Washington University. After serving in Europe, he became the Army’s deputy chief of staff for operations and planning at the Pentagon before being named Army chief of staff.

After his retirement from the Army in 1983, Gen. Meyer served on advisory panels for the White House and Pentagon and was president of Army Emergency Relief, an organization that provides assistance to soldiers and their families. He also served on several corporate boards and the boards of the Hoover Institution and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Gen. Meyer was a physical fitness advocate and often played tennis with President George H.W. Bush. He was the Pentagon handball champion in his early ’50s, while serving as chief of staff.

Survivors include his wife of 64 years, the former Carol McCunniff of Arlington; five children, Tom Meyer, a former editorial cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle, of Asheville, N.C., Tim Meyer, a retired Army Reserve colonel, of McLean, Va., Doug Meyer of Marlborough, Conn., Nancy Meyer of New York City and Stuart Meyer of Horsham, Pa.; a brother; seven grandchildren; and a great-grandson.

When he stepped down as chief of staff in 1983, Gen. Meyer said he would not miss jousting with Congress over funding and weapon programs.

“This is Meyer’s personal view,” he said, speaking of himself in the third person, “but I don’t mind telling Congress how to do business since they’ve been telling me how to do business for the last few years.”

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.18.0