OBITUARY

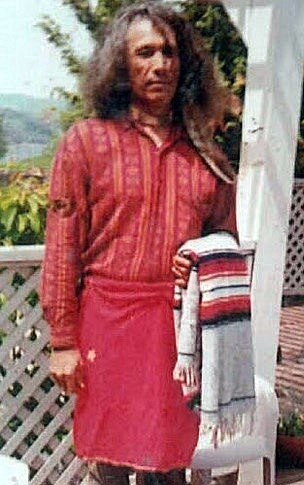

Francis "Frank" Carlos Wood

15 November, 1943 – 20 December, 2018

Francis (“Frankie”) Carlos Wood, 75, passed away on December 20, 2018, having come into this world on Nov. 15, 1943. Frankie was a proud son of Barrio Anita, where he was born and raised, and of Barrio Hollywood, where he was rooted during his very productive Chicano organizing and activist years. Preceded in death by his parents Concepción González and Pierre Stirling Peyrón Wood, his brother Carlos (“Butch”) Burruel, and his sister Mariana Alexander. Frankie is survived by his wife Cecilia Vega Wood, son Frankie, Jr. (Meliza), daughter Sondra Wood Gil (Robert J.), son John (Belin Lira), sisters Connie Hendricks, Cecilia Evelyn Bartreau, Silviana Wood, Olga Arvizu, brother Willie Wood, 11 grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and many nieces and nephews.

Frankie was multi-dimensional. He was a passionate gardener and was “quite the botanist and horticulturist.” He was a committed environmentalist, on a personal as well as a political level. Although he had no formal schooling beyond high school, Frankie was extremely well read. An unrepentant raconteur, Frankie could cite the Bible, Shakespeare, the great philosophers, the classics, contemporary political pundits, and others in between. And he did so naturally, with no airs. Frankie always had a transistor radio with him, tuned to the local NPR (National Public Radio) station. He loved to listen to classical music, and he kept up with the national and local political, social, and cultural dynamics of the times, about which he was never shy about sharing his opinion. Frankie loved cats and always had one (or more) around for company. Over the years he rescued many felines. While not religious in the “go-to-church” sense, Frankie was very spiritual. Believing that all faiths had a richness, he was spiritually ecumenical and embraced all faiths.

Part Yaqui on his mother’s side, Frankie fully embraced his indigenous heritage and had a deep respect for indigenous peoples, culture, beliefs, and traditions. He participated regularly in sweat lodges so as to cleanse his mind, body, and spirit. Frankie spent six years in North Dakota, working with and among the Dakotas (part of the Sioux Nation). Frankie’s attachment to the earth and its fruits was rooted in his indigeneity.

Being human, Frankie was not perfect. He made many mistakes and bad life decisions. But he had the integrity and presence of mind to recognize this and to work to ameliorate the effects of these. A constant in Frankie’s life was his love for his children. Even when Frankie was apart from them, his daughter says she and her siblings could feel his love and sense his presence. That he was able to reconnect with his children brought joy and peace to Frankie as he approached the end of his earthly existence. He would always ask about his “little seedlings,” as he called his grandkids. Although he didn’t get to be surrounded by them, it made him happy to hear about them.

Just as Frankie loved—his children, the earth and its fruits, cats, his indigeneity, etc.—there were things he hated. He hated injustice. He hated intolerance toward people who were deemed to be “different” and were mistreated and discriminated against because of who they were. He hated that politicians and policy makers misused their authority to the detriment of people and the environment.

But Frankie did not just complain. He had a “take charge” aspect in him, which moved him to action. In the late 1960s Frankie founded the Young Mexican American Association (YMAA), which was based at Oury Park in Barrio Anita and later moved to a storefront on Main Avenue and Second Street, the old El Cortez market, which was named “Quinto Patio” (“quinto patio” is the poorest part of a neighborhood).

YMAA had two main purposes. One was to keep young Chicanos out of trouble with the law and to create educational and employment opportunities for people who, in Frankie’s view, had been cheated by the schools and society out of a fair shot at a decent life. Frankie believed the schools instilled an inferiority complex in Chicanos, which led to self-destructive behavior. Frankie held study sessions on Mexican/Chicano history and culture so as to instill ethnic pride and a high self-esteem to motivate the YMAA members to develop their potential. In the late 1960s, Frankie was working as a City of Tucson garbage collector (a “tirabichi,” as they were known) and soon became a one-person equal-opportunity office for fellow tirabichis and other City workers who were being treated unfairly with respect to reprimands and promotions.

Frankie was a moving force in the local Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. Because of the energy and passion he exuded, a newspaper article described Frankie as a “firecracker.” Frankie was a key player, an integral part of the leadership, in the historic “El Rio for the People” movement of 1970 that created the El Rio Neighborhood Center and Joaquín Murrietta Park, which have become barrio anchors. “El Rio for the People,” which empowered westsiders to stand up to City Hall and demand respect and established once and for all that we will no longer be sent to the back of the bus, has been described as “a defining moment in the political evolution of the west side.”

Another product of the Barrio Hollywood-based “El Rio for the People” movement and Chicano Movement is the concept of community policing in Tucson. Frankie was intimately involved in the efforts to convince the Tucson Police Department to establish satellite offices in the barrio and have culture-friendly (e.g., Spanish-speaking) cops staff those satellite offices. This resulted in the first-ever barrio TPD satellite office—called “Adam 1”—being set up in Barrio Hollywood. Today there are several such neighborhood-based TPD satellites. Frankie was one of the chief architects of an initiative in which we—the Chicano Movement—insisted that chain stores and other “outsiders” that did business in the barrio should hire people, including managers, from the barrio under threat of a boycott of their business.

The above represent only a sampling of Frankie Wood’s contributions to our community. Frankie’s DNA and fingerprints are all over many of the advances we achieved for the Tucson Mexican American community in the 1970s, the halcyon days of the Chicano Movement.

After those halcyon Chicano Movement days, Frankie moved to California, where he remained active. He was involved in a coalition to save the redwood trees from destruction, and he became an organizer for Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers union and for a time was one of Chavez’s bodyguards. Frankie returned to his beloved Tucson in 2004.

Frankie Wood may not be a household name, but our community owes him a huge debt of gratitude for the work he did on our behalf.

Francis (“Frankie”) Carlos Wood—Presente! Que en paz descanse (QEPD) nuestro fiel guerrillero. May the Creator light his path on his final journey.

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.18.0