OBITUARIO

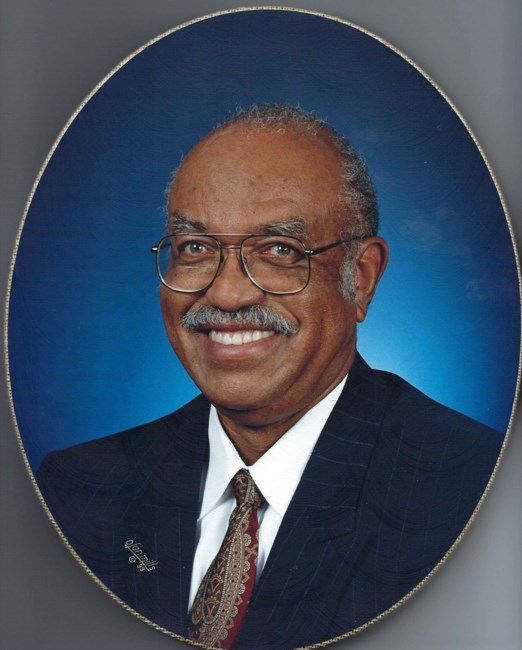

Johnny Mack Perdue

20 junio, 1938 – 23 septiembre, 2025

Johnny Mack Perdue was the first child born to the late Louie Mack and the late Rowena Bradley Perdue in Andalusia, Alabama. The second child born to this union was Corene Perdue Ross (deceased) and Helen Voncile Perdue Owens. He graduated from Covington County Training School; he worked on the family farm throughout high school into college then attended Tuskegee Institute (Now Tuskegee University) where he obtained a degree in Agricultural Economics. He relocated to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he was employed at the University of Nebraska with the USDA's Agriculture Research in the area of Entomology. He enlisted in the US Army, spent two years in Augsburg, Germany. Upon his discharge from the Army, he returned to his former job at the University of Nebraska. Johnny married is wife, Frankie Toussaint, on December 29, 1962, to that union were born two children John Derrick Perdue and Carmen Perdue Francis. Johnny had a 41-year career with the United States Department of Agriculture as a County Supervisor with the Farmers Home Administration where he retired in 2002. After his retirement he served as treasurer of the First Baptist Church in Greeley, Johnny had a deep passion for gardening, he was very generous with the produce from his garden, donating hundreds of pounds of produce to the Weld Food Bank and sharing with family and friends. He and his wife enjoyed making jams, jellies, other fruit preserves Johnny and his wife Frankie enjoyed traveling both in the United States and to many countries.

Johnny leaves to cherish his memory, his wife Frankie, Son John Derrick, daughter Carmen Perdue Francis (George Francis,IV) four grandchildren, Jenaya LaVon Perdue, (John Louie Toussaint Perdue, deceased) George Francis V, Grayson Francis, Gianna Francis. A Godson, Chase Lessman. A sister Helen Voncile Owens (Jimmy Owens) three nieces, Akecia (Terry) Cunningham, Felicia Adams (Chris), La Joya Toussaint, three nephews Jerrod (Arnice) Owens, Ehren (Shanteria) Owens, Charles E. Ross (Valerie) a brother-in-law Arthur Lee Toussaint, sister-in-law, Sharon Polk and a host of cousins.

Johnny died on September 23, 2025 following a brave fight with pancreatic cancer. Funeral services will be held at the First Congregational Church of Greeley, 2101 16th Street on Thursday October 2, 2025 at 10:00 AM with burial at Sunset Memorial Gardens.

Johnny was a gardener at heart and in keeping with his passion, in leu of flower arrangements, please purchase live plants from Morgan Floral Company 1.970.353.1712 or visit their website for delivery to the church location. Memorial contributions in Johnny's honor may be made to the Weld County Food Bank: https://weldfoodbank.org/donate-now/

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Granddaughter’s Reflections

Jenaya L. Perdue Ed.D

One thing that Grandpa knew was life. And cycles. And rest. And harvest. And sowing. And tilling. And plowing. And planting. And dying.

Sacred phone conversations that remember differently are when he would randomly ring me in July and say, “Collards are about done.” What I heard then was, “I’m about to eat good at the grandparents’ house real soon!”

What I hear, recollect, and remember now is, “I planted seeds months ago so that you can eat in abundance now. I planned and cultivated my plants so that you would be full and not hunger. I labored so that you can refill and go along your own path. I did my work so you can do yours.”

Grandpa knew every square millimeter of his garden. It was his sanctuary, his respite, and his legacy. He spoke 10 words in a conversation. Maybe 8. HIs plants spoke for him. “Spoke” is too banal of a word—downright offensive—for his plants sang 5-part Bach fugues, resounded with the sheer overwhelm of an entire majestic symphonies, exhaled Pulitzer Prize poetry, and also just bloomed and faded in the Greeley, Colorado breeze.

He would laugh silently with his shoulders reaching his ears. His laugh was a family favorite.

His mind was always calm and regulated. His soul never far from those garden lines of peas and greens and zucchini and squash and beets and corn and carrots and tomatoes. Although his body would be sitting at the Thanksgiving table or listening to the news of the day, he was communing with his garden. Thinking about cycles and the waning and the weeds and the soil. In my fully conjectured, completely unprovable conclusions and projections (and you can’t convince me otherwise), when I saw him with belabored final breaths out of exhausted lungs, I think even then he was pontificating about those soft, forgiving planting rows he walked, dropping seeds and pruning weeds and harvesting and cycling.

As I became the thinker and writer that I am with my soapboxes resulting from processing where I’ve been planted, I often wondered how he did not rage. He saw, experienced, knew, and journeyed more than me. Yet, he seemed untethered and unbothered. I thought a few years ago about asking him. As I formed the words and found the bravery to ask him a deep question whilst sitting at his dining room table, “Grandpa, how are you still standing and not raging everyday? How do you not just flip tables and yell and scream about the problems in society? How can you be calm, collected, and unbothered in times such as these? Are you calm, collected, and unbothered??” I inhaled, gathered my britches to inquire, and got out a barely audible “Hey gran—“ from my dry, chapped lips and throat. Decibels far too small to reach his ear. He stands up from the table, grabs his pocket knife, and disappears. I was like, “Welp, that was my chance. I’m never gonna get my answer—my wisdom nugget I could hang onto in these tumultuous times full of outrageous, relentless nonsense and chaos.” 5 minutes later, he comes back with a zucchini the length of my femur.

That was my answer. Not just for what I was about to ask. But for questions I don’t even have yet—questions that will take decades to finally peek through the top soil of my mind and spirit.

Grieving a death is not something we do well here in the west. Death is hard. It’s final. It can be vile. Unexpected. Ugly. Death is unavoidable. Death is necessary. Death is the flip side of birth. Death is the garden. We can never have flowers and collards and pretty things if nothing ever dies. We will never have a harvest without something or someone becoming an ancestor. We can never see the fruits of our labor without pruning. We must make hard decisions in order to bring forth abundant life. Grandpa knew this. If you’ve ever eaten a bowl of turnip greens at 2813, you know this also. Death is sacred and hard and beautiful just as much as the seedling and the spring blooms.

In those twinkling green eyes and that resolved tenor voice of his, when he called me to tell me, “The collards are done.” The unspoken part was that of the deepest love, care, and compassion, “Come eat what I planted so you can go do your work.” He now says to us, “I am now done. I am not alive. I am an ancestor. Remember my garden, remember what I showed and taught you so that you can go do your work.”

Muestre su apoyo

Comparta Un Recuerdo

Comparta

Un Obituario

Obtenga actualizaciones

DONACIONES

Servicios

COMPARTA UN OBITUARIOCOMPARTA

- RECIBIR RECORDATORIOS

v.1.18.0