AVIS DE DÉCÈS

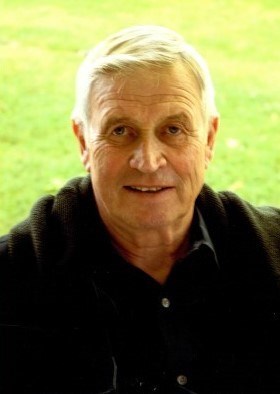

David L. Grumman

19 septembre 1934 – 3 janvier 2025

David Leroy Grumman Sr., who impacted the energy efficiency and indoor air quality of buildings worldwide as founder of a nationally recognized engineering firm, died peacefully in his home on Jan. 3 at age 90. David also was a civically engaged Evanston resident, avid sailor and squash player.

Amid sharply rising gas and electricity prices and a looming energy crisis in the early 1970s, it occurred to David while shaving one morning that building managers would benefit from more efficiently designed mechanical systems, thereby reducing their energy consumption, operating costs, and environmental impact.

In his first job after college at an architectural firm, David designed mechanical heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning systems for large commercial buildings. “I knew a lot about building systems and what made them tick, or at least I thought I did, so in early 1973 I decided to start such a firm,” he said. He named it Enercon to underscore the firm’s focus on energy conservation.

He opened a small, three-room office on Church Street in Evanston, and his wife, Blair Perkins Grumman, worked as his unpaid, part-time assistant. Within a year, David’s shaving revelations proved prescient, and he needed to build staff. A fortuitous recommendation from the University of Illinois’ Mechanical and Industrial Engineering School introduced him to nearly graduated Al Butkus, who was hired to start at the end of the school year.

Under this partnership, Enercon expanded steadily. In 1982, the duo renamed the firm Grumman/Butkus Associates (GBA). Today, GBA boasts over 150 employees in four offices across the country. The Evanston-based firm specializes in sustainable, energy efficiency consulting for large institutions, from hotels, to universities, to hospitals. David’s impact on building codes worldwide, including the new standard used to ban indoor smoking, was underappreciated, according to GBA Chairman Dan Doyle. His work developing such standards, where none had before existed, came via David’s committee leadership roles at the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ASHRAE’s standards would later be widely adopted by public buildings. For years, David withstood vehement and widespread objections from industry groups, particularly tobacco lobbyists, who fought against the new standard. "This was groundbreaking. This standard altered the course of new building design and major renovations ever since," Doyle said. "Every building energy code around the world owes something to David's work and leadership. Before his work, there was no bar and no limitations on building energy efficiency.”

Born in New York City but raised in Port Washington and Plandome, Long Island, David was the youngest of four children of Rose and Leroy Grumman, founder of Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp. David quickly learned to share his father’s love of sailing, building mechanical contraptions in their basement, and solving engineering problems. Ironically, when asked why he didn’t follow in his father’s footsteps and learn to fly airplanes, David said that his father thought flying was “too risky.” Instead, he focused his leisure time on land and sea-based activities. David learned to sail as a child and his love for sailing continued throughout his life. He enjoyed family cruises on the Grumman family’s 46-foot Alden ketch. As a teen, he skippered his 19-foot Lightning, Black Panther, in competitions in Long Island Sound and, later, along coastal towns of New England.

He attended Deerfield Academy in Western Massachusetts beginning in 1948, where David’s love of sports – specifically soccer, squash, and lacrosse – flourished. He met Blair Perkins of Evanston at a college party while both were undergraduates at Cornell University. The two began to study together; he engineering, she government. Blair was a shy, studious, and talented pianist; David was a Naval ROTC engineer and triathlete, finding time to play on the varsity soccer, squash and lacrosse teams. David’s role on Cornell’s lacrosse team, aside from being captain, was to hover around the opposing goal and score. One such matchup found him competing against a powerful Syracuse team that included the legendary future NFL Hall-of-Famer, Jim Brown. David recalled “bouncing off” of Brown while chasing a loose ball. David’s love of squash lasted well into his 70s, by which time compounding aches and pains from decades of athleticism finally ordered his surrender.

Like his father, David earned a degree in Mechanical Engineering from Cornell. To relieve the demands of his studies, sports, NROTC, and an active social life, he found time to catch up on sleep during his “Weights and Measures” class. While Blair and David’s fondness for each other grew, David learned of the Perkins family’s mutual interest in sailing during a visit to Ithaca by her father Lawrence. With his interest piqued and upon learning that Larry Perkins coincidentally owned an Alden schooner, Blair and David’s fate was sealed.

In 1958, the couple married in the days between completion of their undergraduate programs and the start of David’s officer commission in the U.S. Navy. Blair and David relocated to Charleston, South Carolina, where David served for two years as a lieutenant and engineer on the USS Bold minesweeper. While David interned one college summer at Grumman Corp. where he worked on the F7F Tigercat, he decided not to pursue a career there, choosing instead to carve his own engineering path.

Once settled in Evanston, David began work at his father-in-law’s Chicago-based architectural firm, Perkins & Will, where he ultimately oversaw the firm’s engineering standards as well as its 50-person department of mechanical engineers. On weekends, David strapped a Butterfly sailboat to the top of his Chevy Impala and drove off to a small man-made lake, where other area Butterfliers gathered to race. A complicated pulley system he crafted from the ceiling of the garage allowed him to effortlessly raise or lower his boat onto the car. From his basement workshop, David rebuilt his childhood Lionel train set, refurbished Blair’s childhood doll house for his own children, created a two-story outdoor playhouse, and fixed anything that broke.

David shared his time and expertise to strengthen the City of Evanston, with service on the Evanston Plan Commission, Evanston Energy Commission, and Evanston Utilities Commission. He also served on the boards of the Grumman Corporation, WTTW/Channel 11, the Community Hospital of Evanston, and the Ellis L. Phillips Foundation. The family summer cottage in Charlevoix, Michigan provided a base of operations for sailing, swimming, golf, and tennis, as well as boisterous family gatherings and, occasionally, David’s specialty homemade deep dish pizza - a daylong production. He continued to sail on the family’s 36-foot ketch, Allouez, that was moored in Charlevoix. He particularly enjoyed day sails on Lake Charlevoix and extended cruises with family and friends to Lake Huron’s North Channel and Georgian Bay, Lake Michigan, and Lake Superior.

Following the 2003 death of Blair Grumman, David became reacquainted with fellow Evanston resident and artist, Mary Ann Pollard. By 2005, they married. In 2020, as the burdens of caring for a 160-year-old historic home became too much, David and Mary Ann moved into an independent home in Westminster Place in Northwest Evanston. In addition to his wife, Mary Ann, David is survived by his three children Roy (Susanne), Cornelia (Jim Warren), and Eleanor (Michael Husman), and six grandchildren.

A Celebration of Life will be held on Saturday, January 18, 3:30 PM, at the First Presbyterian Church of Evanston, 1427 Chicago Ave, Evanston, IL. In lieu of flowers, donations to honor David’s memory may be made to the McGaw/Evanston YMCA, mcgawymca.org/donate/.

Montrez votre soutien

Envoyez Vos

Condoléances

Partager

L'avis De Décès

Obtenir les mises à jour

Prestations de Service

Partager l'avis de décèsPARTAGER

- RECEVOIR DES RAPPELS

v.1.18.0