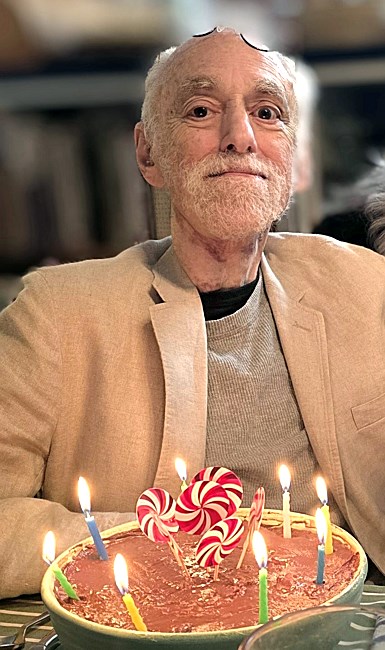

OBITUARY

Alec Charles Dubro

November 4, 1944 – January 1, 2025

November 4, 1944 – January 1, 2025

In June of 2018, Alec Dubro woke up in a Johns Hopkins Hospital recovery room after an operation to treat a recurrence of neck and throat cancer. He had a large bandage on the right side of his neck and a giant scar with staples down his chest, where they had taken tissue for a skin flap.

He cracked open an eye. “Is Trump still president?” he asked the attending nurse. “Yes,” she said, and laughed.

Alec shut his eyes: “Put me back under!”

“That’s when I knew he had survived the ordeal,” recalled Kim Fellner, his spouse of 33 years.

Alec Charles Dubro, a lifelong freelance writer and a former president of the National Writers Union, died on January 1, 2025, at his home in Washington, DC. He was 80 years old or, as he would say, “too old to die young.”

The cause was decline from the unintended consequences of neck and throat cancer treatment.

Born in Brooklyn, NY, and raised in Richmond, VA, Wheaton MD, and Pittsfield MA, Alec always marveled that he had lived to grow as old as he had. As a student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and resident of San Francisco and the East Bay for 17 years, he was an early adopter of the “sex, drugs, and rock and roll” ethos of the late 1960s and early ’70s. Many of his recollections from those days involved nerve-wracking petty drug runs, decrepit cars, beloved motorcycles, and sketchy living situations. The excesses of that era left their mark in a permanent hearing impairment and a lingering flirtation with drugs and alcohol, although, at the time of his death, he hadn’t had a drink in more than 35 years.

But that formative period also provided him with a philosophical and political grounding and a dark humor that he put to good use in a long and varied career as a writer/researcher and commentator on the sociopolitical scene. That humor also saw him through years of medical and health-related tribulations, including the inability to eat much solid food.

Alec moved to San Francisco in 1968 hoping to become a rock and roll writer. He got his wish, contributing to a feisty new publication called Rolling Stone, where he reviewed concerts and records by the likes of Elton John, Linda Ronstadt, and Sly and the Family Stone.

After four years as a music critic, Alec transitioned to writing political and social features, while working odd jobs ranging from census taker to private investigator. In 1980, he joined the Center for Investigative Reporting in San Francisco and eventually co-authored (with David E. Kaplan) Yakuza: Japan’s Criminal Underworld, a book on Japanese organized crime with a long in-print life and editions in nine languages. He was subsequently a consultant to the President’s Commission on Organized Crime and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

In addition to Rolling Stone, his articles appeared in the Washington Journalism

Review, Village Voice, Mother Jones, Science Digest, New York Observer,

California Lawyer, San Francisco Examiner, New York Newsday, as well as in Japanese publications such as Views, Friday, Focus, and Sapio.

In 1985, he relocated to New York and moved up the ladder in the National Writers

Union (NWU), serving on the board and then as president from 1987 to 1990. His time at the NWU was marked by organizational growth and crystalized his enduring commitment to the labor movement. He also fell in love with Kim Fellner, the union’s first executive director. Although the romance spelled an end to their tenure as NWU officers, the marriage flourished for the rest of his life. The two moved to Washington, DC in 1993, where he wrote for labor unions and nonprofits – everything from policy and blogs to comics – as well as articles and opinion pieces. As an accomplished researcher, he also held staff jobs at think tanks and labor institutes, including the Institute for Policy Studies and the Communications Workers of America.

Alec was known for nurturing friendships, a fair number dating back to his college and California years. Many of his friends were initially drawn to his quick wit, impeccable comedic timing, and recall of esoteric factoids, not to mention an uncanny knowledge of geography. (It was generally agreed that Alec knew everything.) But under that occasionally biting front, he was generous and insightful with the people in his life and championed a humanistic and progressive worldview.

Alec had always been a good photographer, and the Internet and Photoshop proved a perfect outlet both for Alec’s visual sense and for his satirical edge. His first major foray into online comms was The Washington Pox, a listserv publication purveyed to friends and colleagues. He soon moved to Facebook, where his disregard for political correctness on all fronts occasionally led to heated exchanges and landed him in Facebook jail. But mostly he gained a wide following of friends, old and new, who found his subversive sense of humor, and sometimes off-the-wall silliness, a welcome antidote to grim headlines and pompous political blather. His series featuring Chris Christie in his beach chair cleverly inserted into varied works of art is still a favorite among his online admirers.

In addition to his wife Kim Fellner, Alec is survived by his sister Julie Marino and nephews Peter and Brian Marino; by his close cousin Zenaida Pelkey; and by his in-laws, Gene Fellner, Jane Fellner, and Neal Friedman, and nephews Sam, Gus, and Leo Friedman. The family thanks his care companion, Seth Levin Nosanchuk, for his assistance over the past year, as well as the vibrant community of friends that lavished Alec with love and support.

In life, in politics, and in humor, Alec personified leftist Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s pessimism of the intellect and optimism of the spirit. Or as one of his friends put it, “It’s going to be harder to live through the second Trump administration without his sharp, principled, original voice to cheer us on.”

Show your support

Add a Memory

Share Obituary

Get Reminders

Services

SHARE OBITUARYSHARE

- GET REMINDERS

v.1.18.0