AVIS DE DÉCÈS

James Cameron Orr

10 août 1930 – 22 juillet 2022

One day, not so long ago, Jim climbed eight flights of stairs as part of his daily exercise routine, did the sudoku from the newspaper and paid bills on the computer. He scolded for poor behaviour his new Siamese kitten, Rho — named not, as he would carefully point out, for the Greek symbol but rather as an abbreviation of rhodium, his favorite chemical element (helpfully elaborating that it’s “a rare transition metal named for its rose color”). Most people didn’t respond to this, which mystified Jim: he loved chemistry above all else — well, above all else except one. But that comes later.

Born in Paisley, Scotland, in 1930, Jim was raised in the notorious Gorbals district of Glasgow. Here he shared a one room tenement with his mother, two siblings and an ancient relative. It was a contradictory sort of place, simultaneously primitive and violent, yet curiously proper, almost prim. Nightly drunken squabbles — the gang fight had been invented there, Jim claimed — yielded in the day to streets safe enough for a single female to walk unaccompanied. Schools were filled with poorly dressed youths but also, crucially, kind and dedicated teachers. All in all, it was a happy period, and he remembered it fondly despite the poverty.

No matter. Jim was curious about everything, and even at a young age had a defining disregard for prevailing thought. His peers thrilled to sports, which he found boring; they slept through chemistry, which he loved, captivated by the unique beauty of the elements and the way they “held hands” to form molecules. He liked music and Latin and archeology too, suggesting a stereotypical nerd. He wasn’t one, though, just a good-looking, vigorous guy with many friends who happened to have a preternaturally well-developed internal compass. Jim excelled on the standardized Eleven-plus exam and was directed into the academically rigorous grammar school stream. After a couple of years of national service rescuing downed RAF aviators, he entered Imperial College in London against the will of his father, who took a dim view of “university types” and refused to provide support. Undeterred, Jim managed to cobble together just enough from scholarships and construction jobs to complete his degree. Considered promising, he was steered towards a graduate position in one of Imperial’s most prestigious labs.

Stubbornly, Jim had ideas of his own. He wasn’t interested in joining a lab with a stellar reputation. It was what went on inside that mattered, he thought, and he’d been reading papers from a professor whose work he thought underappreciated. Derek Barton pictured molecules in a way that Jim found exciting, as living structures in three dimensions, not as the traditional line drawings confined to two-dimensional sheets of paper. Joining Barton’s lab was a fortunate move, resulting in a highly regarded Ph.D. in steroid biochemistry. It would pay off in other important ways, too.

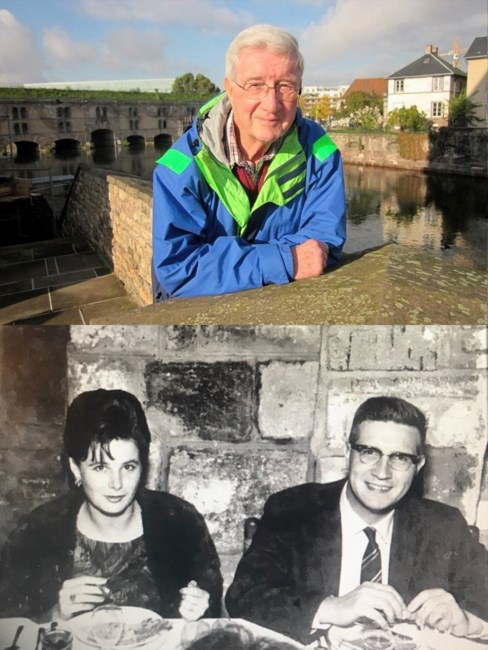

To start with, Jim’s doctorate opened doors at the Rockefeller Foundation, which funded a post-doctoral year at Iowa State University, halfway around the globe. He arrived with his usual serious mindset and deep, almost obsessive, work ethic, but quickly became distracted for reasons that had both everything and nothing to do with chemistry. As he lunched in the international students’ union one day, Jim was introduced to a luminous Australian Fulbright scholar named Robin Moore, who’d also travelled halfway around the globe, albeit from the opposite direction. She was a great beauty, with a passing resemblance to Audrey Hepburn, but it wasn’t that — at least, not mainly. They shared a taste for Bach and open-ended questions that invited exploration about any subject at all, usually starting with, “I wonder why …”. Neither had any patience for intellectual conformity or pretension. Both were engaged to others at the time, quickly broken off. Their union was not just a marriage but the kind of romantic and intellectual pairing against which others are measured. It’s not clear who proposed to whom. Jim could never believe his luck and judged her the smarter of the two.

The newlyweds were soon off together on an adventure. The world had a longstanding problem with fertility: too much, not too little, and unpredictably timed. Steroid-based medications offered a potential solution; as a result, those skilled in their synthesis were in demand. Thus, Jim moved to join an eclectic multinational research group led by a charismatic prodigy named Carl Djerassi at the Syntex Corporation based, of all places, in Mexico City. It was an extraordinarily rich expatriate life. Highly productive science filled the days — Jim was named on fifteen patents in a two-year period — yielding on nights and weekends to Mexico’s infinite cultural attractions. Jim and Robin became fluent in Spanish, developed a huge love for the country and its people, and two children came along, Andrew and Fiona. The fruit of his group’s research, the oral contraceptive pill, was approved by the FDA in 1960.

Meanwhile, the world had caught up with Jim’s assessment of Derek Barton, who was later awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry. On the way there, as his stature grew, Barton was often asked to suggest candidates for open faculty positions. So it was, in 1962, that when Harvard was looking for a steroid biochemist, Barton suggested Jim. He flew up for interviews during the Cuban missile crisis, against Robin’s wishes, and was hired.

Twelve busy and happy years followed. Boston might not have been the exotic cultural experience of Mexico City, but it was just as vivid in its own way, a swirl of brilliant colleagues and colorful, inventive characters in the mold epitomized by Richard Feynmann, the physicist whose irreverent science books delighted Jim and were frequent gifts to his students. He set up Harvard’s first gas chromatography - mass spectrometry unit, a device so delicate that he often stayed up with it through the night when no one else was around because rumblings from the building’s elevators ruined his experiments. Jim established a reputation for not publishing anything other than first-rate work, and was a popular undergraduate tutor at Quincy House, off Harvard Square. He was later joined in this role by Robin, who’d taken time off to raise the kids and then enrolled at Harvard herself, receiving master’s and doctoral degrees in public health. They developed a full life outside academia, becoming dedicated Scottish country dancers and buying a cherished Edwardian-era cottage on Sebago Lake in Maine that Jim filled with quirky Rube Goldberg devices designed to solve various problems, large and small. Both were frugal but they travelled widely, generally to obscure places, dragging along the kids. Somehow there was always money to buy books, if few other luxuries.

The awarding of Robin’s doctorate precipitated a fresh new adventure. Now that she was fully qualified, Jim was determined that they should look around for places willing to hire them both. A new medical school had just been launched at Memorial University of Newfoundland. It was delighted to hire two well-pedigreed birds with one stone, so to speak: Jim as the Associate Dean for basic sciences, and Robin as a professor in community health. By now a recognized world authority in his area, Jim set up a lab and plunged into teaching at all levels, always hopeful that if he could just deliver the perfect lecture his audience couldn’t help but be inspired to love chemistry too. He endeared himself to medical students by camping out in the medical library on the evening before the feared biochemistry final exam, making himself available for last-minute questions. A devotee of the Icelandic Sagas, Jim could also be found at seminars in areas as far afield as linguistics and folklore, often making a genuine contribution. Finally, he became a capable and effective administrator. Here, however, Jim found the endless bureaucratic cycle of meetings, interpersonal disputes and petty dustups over lab space to be not just dull, but stressful, turning his hair a snowy white. Fortunately, his contract included a clause that allowed a full-time return to his beloved lab, which he happily exercised after five years, and the healthy brown colour returned.

When Jim and Robin arrived in Newfoundland, it hadn’t been clear how long they’d stay – five years, they thought, possibly ten. But they quickly warmed to the hardy, authentic people and culture, and the close-knit academic circle – and, suddenly, there they were, twenty years later. On his retirement, a grateful university named Jim Professor Emeritus.

Meanwhile, Robin had acquired a stature of her own, recognized for outstanding service to the promotion of public health in Canada and appointed president of the Canadian Institute of Child Health in Ottawa, where they lived for fifteen years. Afterwards they moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia, nearer to their son, Andrew, settling into a bright condominium near its spectacular harbour and formal public gardens. There were lots of universities, galleries and schools around, and a great symphony orchestra. Jim became a regular at chemistry seminars and Robin was devoted to the proper British brass bands that played on Victorian bandstands nearby. They spent every summer on the lake in Maine, entertaining friends and grandchildren, going to shows, supporting local causes. Public radio was always on in the background. Evenings were filled with ruthless rounds of a bridge-like game named Sandbar near the fire, and open-ended questions starting with, “I wonder why …”. They were healthy and intellectually undimmed, passing for people decades younger, with an outlook to match.

Sadly, the charmed existence couldn’t last forever. In 2020 Robin died, unexpectedly, from a fall. Jim kept up a brave face afterwards but was plainly devastated: they had been married for 62 years, but it was far more than that — a void that couldn’t be comprehended, let alone filled. Still, he carried on without complaint or self-pity, joined by his daughter, Fiona, who moved down from Ontario as the pandemic gathered force. She encouraged exercise, something he had always resisted but came to embrace. The Siamese kitten arrived. There were some health issues, but manageable, and there he was, scolding Rho for an accident. Two weeks later Jim would be dead after a brief illness, on his own terms, surrounded by his children: clear-eyed, unafraid, wondering about things, thinking of Robin. The way he had always been.

James, age 91, of Halifax, Nova Scotia died on July 22, 2022. He was born in Paisley, Scotland, the son of James Orr and Jean Ketchen, predeceased by his wife of 62 years, Robin Moore-Orr and his brother, Euan. He is survived by his sister, Yoskyl, and his children, Andrew (Bianca Lang) and Fiona, and grandchildren Benno and Sophie Orr, and Ian, Cameron and Kellis Malcolm. He was interred alongside Robin at the Camp Hill Cemetery in Halifax, under a monument whose legend declares, “two happy academics, who argued but never fought”.

Montrez votre soutien

Envoyez Vos

Condoléances

Partager

L'avis De Décès

Obtenir les mises à jour

Prestations de Service

Partager l'avis de décèsPARTAGER

- RECEVOIR DES RAPPELS

v.1.18.0